The Jeopardy of Genderswap Storytelling: Un/Becoming Captain Nemo

Observations on Failed Imaginaries, Gender Equality, and the Not-So-Small Matter of Social Evolution or Revolution

The Jeopardy of Genderswap Storytelling: Un/Becoming Captain Nemo

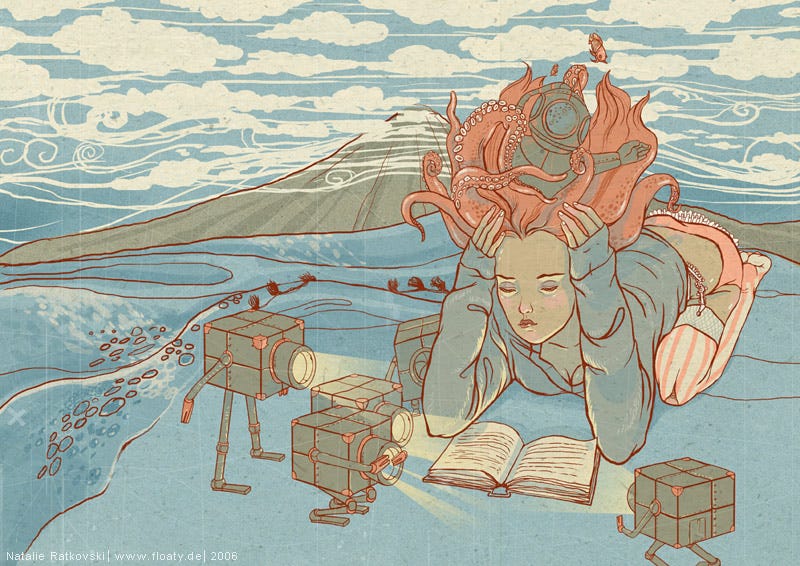

Of all the characters in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comics series, I love Captain Nemo best. What’s not to love about an enigmatic, insurgent, science-pirate who lives in a submarine wrought like a giant octopus, known to us as …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Break to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.